“There are a lot of people who know the price of everything and the value of nothing.” -Oscar Wilde

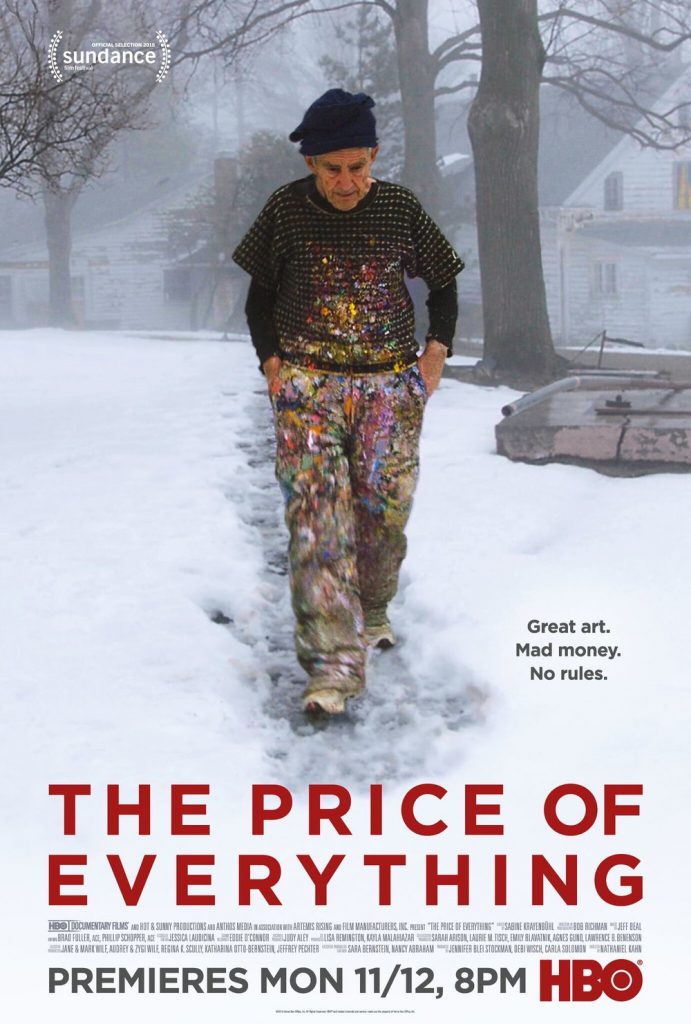

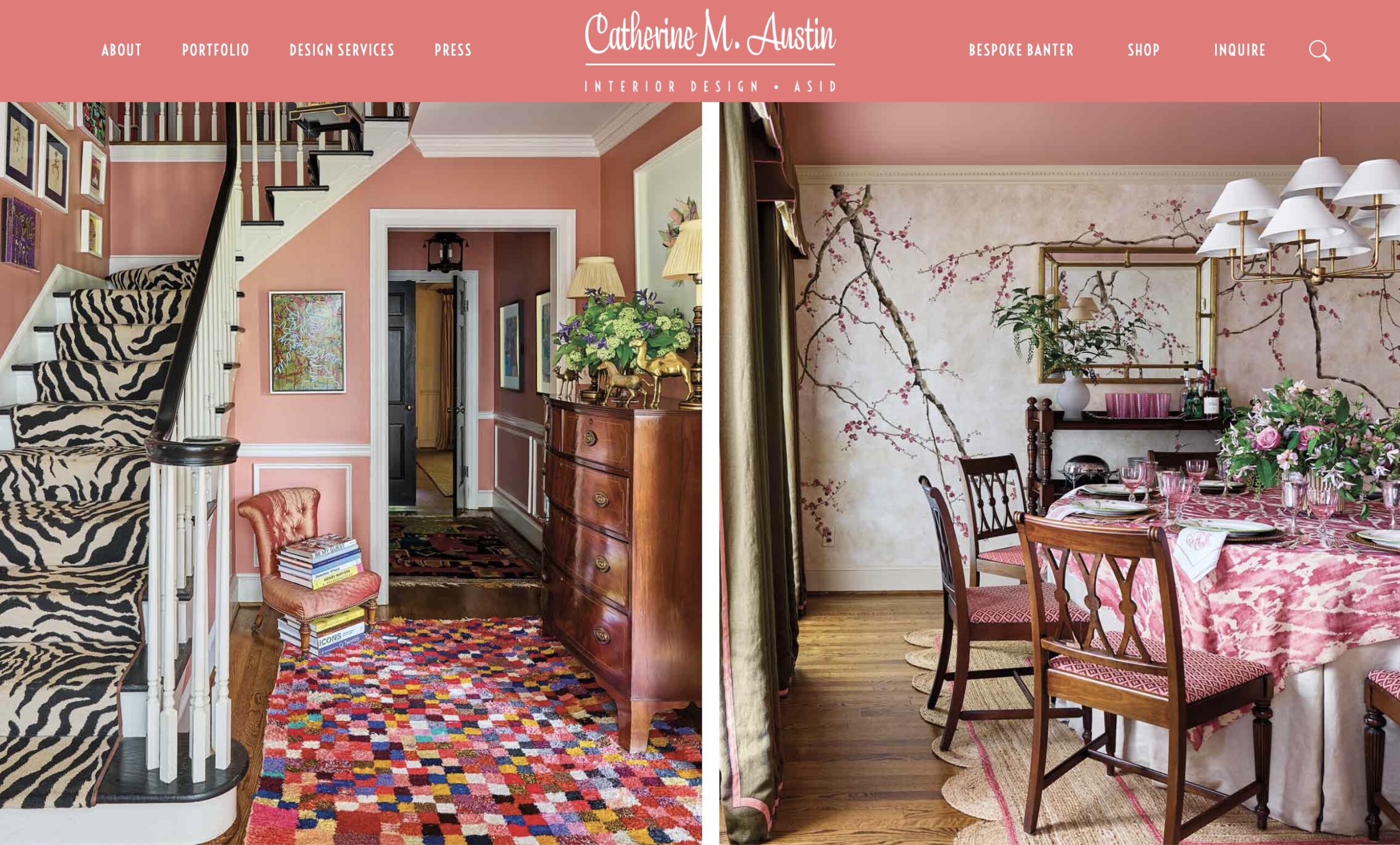

I happened upon an interview this weekend on National Public Radio with Nathaniel Khan, the director of the acclaimed documentary, “The Price of Everything” that appears November 12th on HBO. Garnering accolades from every film festival imagined, the documentary breaks down the boundaries in the art world between artists, collectors, auction houses, galleries, art critics, and more. As a self professed art addict and Sotheby’s alumnae, I cannot wait to see this look behind the curtain. When I introduce works of art to clients, I always address what makes it special and why it is valuable. I am excited to hear their answers to the same questions on a much grander scale.

THE NEW YORK TIMES REVIEW BY A.O. SCOTT

“There are a lot of people who know the price of everything and the value of nothing,” the art collector Stefan Edlis remarks in Nathaniel Kahn’s new documentary. The words, unattributed in the film and the source of its title, come from “Lady Windermere’s Fan” by Oscar Wilde, where they supply the definition of a cynic. But while this colorful and inquisitive cinematic essay on the state of the art world is occasionally skeptical and consistently thoughtful, cynicism isn’t really on its agenda.

Rather than lament the pervasive influence of money on contemporary art, “The Price of Everything” examines the relationship between commerce and aesthetics from different angles. “You can’t have a golden age without gold,” someone says, and by that standard we are currently in an epoch of platinum. The sale and resale of work by living and recently dead artists is a multibillion-dollar market, which bothers some people more than others.

An affable presence just outside of camera range (and the director of “My Architect,” about his father, Louis Kahn), the filmmaker chats with curators and critics, painters and auction-house executives — an impressive cross-section of players with differing stakes in the game. Since all of them do have a stake, none are interested in outright derision or dismissal. There may be arguments over the quality of the bathwater, but everyone agrees that the baby needs protection.

Koons is by some calculations — not all of them strictly monetary — the most successful artist of our time, a consummate self-marketer who brazenly celebrates the commodification of art. It would be easy enough for Kahn to treat him as a villain, but instead he suggest a witty comparison between Koons and an artist whose last name happens to rhyme with his.

Larry Poons lives in a peeling clapboard farmhouse far from Sotheby’s. A star in the ’60s and ’70s, he has fallen out of fashion but has continued to paint, indifferent to trends and less bitter than you might expect. As Koons unveils a partnership with Louis Vuitton, Poons plans a comeback exhibition at Yares Art, an old-fashioned gallery show of colorful, large-scale abstract canvases.

At roughly the same time, Sotheby’s is preparing to auction a collection of paintings that includes work by Condo, Gerhard Richter, Willem de Kooning and other blue-chip names. It also includes a painting by Njideka Akunyili Crosby, a Los Angeles-based, Nigerian-born artist whose reputation is growing. Her presence, like Poons’s, presents an implicit argument against the cynical view that money and celebrity have corrupted hard work and aesthetic value. Even so, the sums commanded by the de Koonings and the Richters are staggering, and their disappearance into private collections feels like a blow to the idea of a democratic culture.

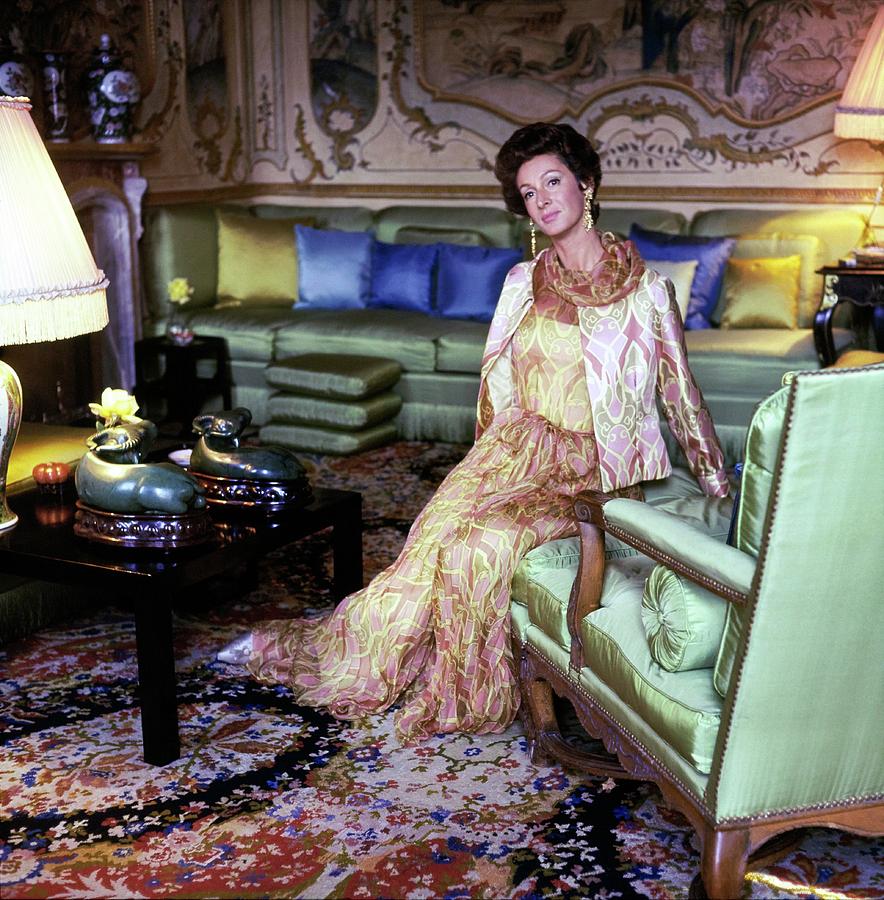

Jerry Saltz, the Pulitzer Prize-winning art critic for New York magazine, regrets that he is unlikely to see the auctioned-off work again in his lifetime. “I’m sad to be saying goodbye,” he says. Equal parts gadfly and cheerleader, Saltz is the playful conscience of “The Price of Everything,” a role he can play partly because he has no money on the table. But if the artists are the heroes, the auctioneers, collectors and dealers aren’t exactly the villains. Their acquisitiveness might be an expression of love.

And they are critics and philosophers of a kind, puzzling over old and stubborn questions. What makes a work of art great? Where does its value come from? Why do we care — as a species and a civilization — about this stuff? According to a figure cited in “The Price of Everything,” those are $56 billion questions. Even at a fraction of that price, they would be just as difficult to answer.