“I felt like a whole person because I could dance.” -Patricia McBride

Weeks after graduating from college, I moved to New York to work at Sotheby’s. For this Southern girl in the big city, it was intimidating to say the least. I was surrounded by incredible works of art, brilliant experts, and glamorous clientele. Many of the decorative objects I handled were worth more than I would make in a year, or even more. One of the perks if working at such an institution was the exposure exquisite culture experiences…we were after all in the center of the universe!

After a string of dating debacles, I met a dashing boy who also hailed from below the Mason-Dixon Line. I knew he was a keeper when he agreed to attend the New York City Ballet with me for a performance of George Balanchine’s Firebird. My boss at the time, the elegant Peter Rathbone of Sotheby’s American Paintings department, would often let us use his tickets. The first time I sat in the amazing seats, I was mesmerized. I had danced growing up, but to watch the perfect syncopation of the dancers with the music along with the elaborate costumes and stage sets by Marc Chagall took my breath away. From that moment on, I tried to attend as the ballet whenever I traveled. I had fallen in love with the sheer joy of dance again.

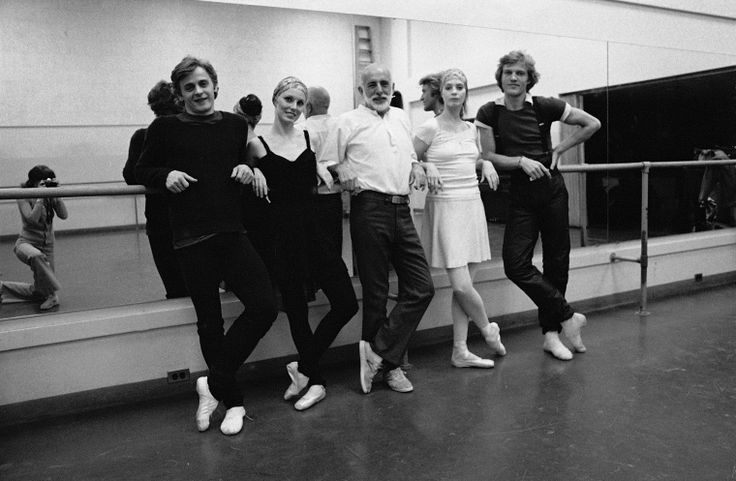

When I moved to Charlotte several years later, I was pleasantly surprised to learn the city had a wonderful dance company….North Carolina Dance Theater, now known as Charlotte Ballet. The incredible artistic directors (also husband and wife) Jean Pierre Bonnefoux and Patricia McBride had both danced for New York City Ballet under none other than George Balanchine. These were dancing living legends right here in my new hometown. They had danced for presidents and world leaders as well as all of the most famous dancers of all time.

This weekend, Patricia McBride is being honored at the Kennedy Center for her contribution to the arts along with Sting, Al Green, Lily Tomlin and and Tom Hanks. Tonight, over 300 of her fans, friends and family came together to celebrate her life and give her a proper send off to Washington.

Mary Curtis, a brilliant journalist and long time fan, interviewed Patricia about her extraordinary life with many of the greatest talents of the 20th century. George Balanchine and Jerome Robbins created and choreographed many pieces specifically for her. She partnered with everyone from Mikhail Barisyhnikov and Edward Villeal to Helgi Tomasson and Rudi Nureyev. In a brilliant grand gesture, event planner Todd Murphy recreated her last New York City Ballet standing ovation from decades ago by orchestrating the audience to shower her with roses once again.The Queen City could not be more proud of this legendary ballerina who calls our lucky city home.

PATRICIA MCBRIDE, PASSING ON BALANCHINE’S TORCH WITH JOY AT CHARLOTTE BALLET

by Sarah Kaufman, The Washington Post

CHARLOTTE — The happiest ballet studio in the world may be the one just down the street from a Rock Bottom Restaurant and Brewery, inside a bright purple building bearing the words “Patricia McBride/Jean-Pierre Bonnefoux Center for Dance.”

Here, on a recent morning, rows of young women and a few young men are being coaxed and praised and sweet-talked into swirling across the floor with luxurious abandon.

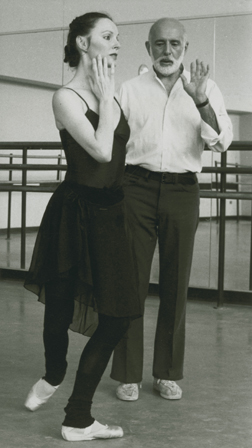

“Good, good! Almost! Just breathe a little more with the arms,” urges Patricia McBride, the former ballerina. She stands at the front of the room, but she can’t resist the urge to move with the music. Her hands and arms weave through the air, her eyes widen on the downbeats.

Keeping still just isn’t her strong suit.

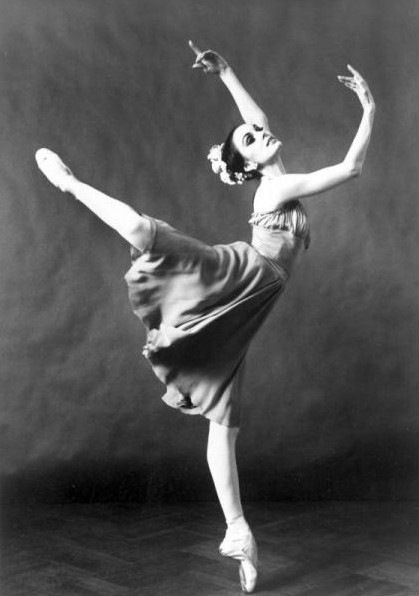

It never has been. In the 1970s, as a leggy, tireless powerhouse, McBride so dominated the repertoire of the New York City Ballet and epitomized its style that she was called “the flag-bearer” of the company.Twenty-five years after she retired from the stage, McBride is still an embodiment of the sheer fun of dancing.

“Soften your arms,” McBride calls out cheerily to these students of the Charlotte Ballet Academy, the training arm of the Charlotte Ballet. McBride is a master teacher at the academy and directs the company with her husband, Frenchman Jean-Pierre Bonnefoux, who like McBride is a former City Ballet principal dancer.

“Breathe through your movements.” McBride demonstrates, stretching her leg forward and tossing an arm high over her head. As she does this, with a broad smile and merry eyes, she makes a little “ah!” sound, a singing, high-pitched inhalation, as if that expansive move from fingers to toes gives her a tickle.

Dancing, even in the gentle way that McBride, 72, does it these days, still flushes her with joy. But then, what doesn’t? McBride’s emotional dial seems consistently set at cheerful. She is delighted, of course, to receive the 2014 Kennedy Center Honor, which will be bestowed in a gala event on Dec. 7. But long before this award, she was known for her dauntless high spirits.

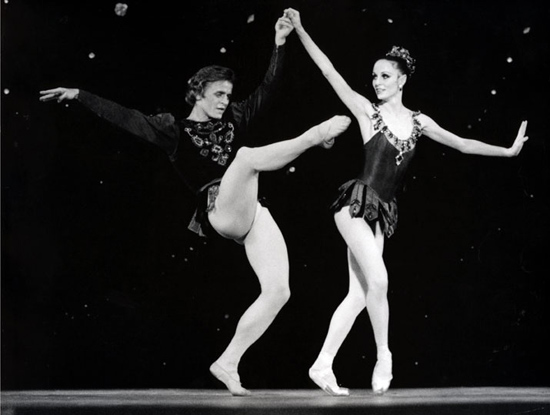

It was her easy, ready-for-anything nature that inspired George Balanchine, founder of New York City Ballet, and Jerome Robbins, the late associate artistic director of the company, to create some of their most enduring works for McBride’s body. She was unusually versatile. Not only was she up for anything, she could do just about anything.This wasn’t so much a gift as an ethic — the payoff, as she’ll tell you, for hard work, though it simply looked like pleasure. Her roles swung from pert soubrettes to artless innocents, from sauce pots to glamour queens and a chilly dominatrix or two. The consistent thread was how she made dancing look like the most delicious experience on Earth.

“She brought something onstage that we can’t even see on videos; that’s what’s sad for me,” Bonnefoux says. “That joy and that need to dance. That pulse. A nonstop commitment to the choreography and the steps. She was in it.”

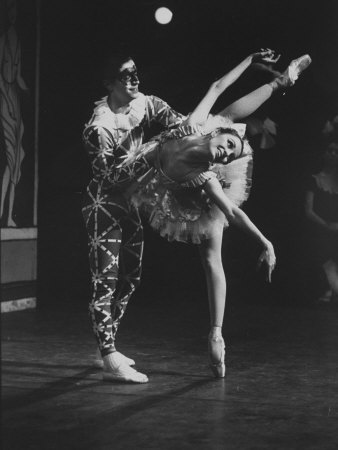

McBride was Balanchine’s first Hermia in “A Midsummer Night’s Dream”; she was the teasing Columbine in his “Harlequinade.” She created the authoritative, pure-hearted Swanilda in his full-length “Coppelia.” For her, Balanchine also choreographed showpieces in the drop-dead sexy “Rubies” section of “Jewels”; in his Gershwin romp “Who Cares?,” in the romantic “Brahms-Schoenberg Quartet” and “Vienna Waltzes,” and more.

She was the rare ballerina who handled Balanchine’s intricate musicality and Robbins’s character-driven mini-dramas with equal ease. She inspired Robbins’s most famous ballets, including his 1969 masterwork on love and youth, “Dances at a Gathering,” which started out as a pas de deux for McBride and Edward Villella, before Robbins expanded it into a larger piece.They rehearsed it five hours a day for 13 weeks, “and I loved every minute of it,” McBride says. Robbins also created parts for her in “The Goldberg Variations,” “The Four Seasons” and “Dybbuk.”

Happiness is powerful. McBride could jolly up the high-strung Robbins, defusing his famously explosive temper.

“She just disarmed him,” says Helgi Tomasson, artistic director of the San Francisco Ballet, who was McBride’s frequent partner at New York City Ballet. “If something went wrong in a rehearsal, she would laugh it off. She’d say, ‘Oh my gosh, I did that? How silly!’ And Jerry would just break into a smile.”

“Ya dum dee da, yup dee da,” McBride sings out in her studio, buoyed by the piano playing and her students. They skitter and bounce across the floor like drops of oil in a hot skillet. She skims along with them, urging them to travel faster, fly higher, jump bigger. Three hours whiz by. McBride teaches her students a bright, springy excerpt from Balanchine’s “Raymonda Variations,” which she first learned from the ballerina Patricia Wilde, for whom Balanchine created the leading role.

So the torch passes; from one body to another. In the ballet world, where the low-tech means of transmitting steps from teacher to student is revered, old dancers never die. They echo in the muscles of the young.

“Glissades can be really exciting!” McBride calls out in her high, soft voice, showing the dancers the beauty of a basic gliding step. It’s a bit like saying the word “and” is really exciting, but McBride makes you believe it. She is zealous about the details: wrists, rib cage, angle of the head. Those little under-appreciated glissades — work them! They are the link to everything you do.”

In the afternoon, McBride turns to her company duties, overseeing “Nutcracker” rehearsals until evening. So it goes, day after day, whether she’s readying the chamber-size, 18-dancer company for the holiday production or for one of its other programs throughout the year, perhaps featuring one of the Balanchine ballets so dear to her.

She and Bonnefoux work year-round. During the summer, they take their dancers up to the Chautauqua Institution in southwestern New York, where the couple run a dance school they founded 25 years ago.

“Are we crazy?” McBride says, leaning on the table over lunch, with her face in her hand. Her deep-set green eyes and broad cheekbones were perfect for the stage, visible from the upper balconies, expressive. With her dark brown hair in a smooth, chic bob, she still has dramatic looks. But her gaze turns dreamy when she’s asked why she keeps working.

“I don’t know. It’s a love, I guess. To show what you’ve got to pass on. . . . I don’t think I’d like to lie around. What would I do?”

McBride takes her pleasure seriously. She’s been drawing a paycheck from dance since 1959, when she joined the New York City Ballet. She was 16. At 18, she became the youngest principal dancer in company history. In her 30-year career, she danced more than 100 different roles. Among her favorites: the zesty “Tarantella” duet; Robbins’s “The Cage” — she was still a teenager when she took on the part of a murderous sexual predator, which embarrassed her, until she grew to love the powerful rush of it. And especially “Brahms-Schoenberg Quartet,” romantic and lush, full of overhead lifts: “The movement was so incredible,” she says. “It evolved from one flowing moment to another.”

After her lavish sendoff from City Ballet in 1989 at age 46 — she was showered with roses, meticulously de-thorned — she jumped into teaching, joining Bonnefoux at Indiana University. In 1996, the couple were offered the job in Charlotte, running what was then called North Carolina Dance Theatre. The name changed to Charlotte Ballet earlier this year, responding to the city’s rapid growth. The ballet has seen a corresponding spike in interest; since 2010, its ticket sales are up 75 percent and donor gifts have tripled.

The couple’s son and daughter both live in Charlotte; McBride and Bonnefoux have three young grandchildren who join them at the ballet school on weekends.

Work is McBride’s life. It is what shaped her, what makes her happy. And it has deep roots.

She never knew her father. She was born in 1942 during the war; he was mostly stationed overseas. Her brother, a composer, was born a year later. McBride has only a dim memory of seeing her dad when she was 3; her parents divorced soon after. Her mother never remarried. McBride grew up with her mother and her mother’s parents in Teaneck, N.J.

McBride’s mother enrolled her daughter in ballet lessons at age 7 “just because it was a nice thing to do,” McBride says.“I always had an inferiority complex, like I wasn’t good enough,” she says. “I was shy. But dancing gave me so much joy, and I was good at it. I felt like a whole person because I could dance.”

When she was 10, McBride’s grandfather died, and her mother, an executive secretary at a bank, became the sole supporter of the family.“I adored her,” says McBride, a bit wistfully. Born of Swiss immigrants, her mother was disciplined and organized, and she never rested. She came home from the bank and took McBride to daily ballet classes.“She instilled in me the work ethic.”

Meanwhile, McBride was getting old-school, apple-pie dance training from a former vaudevillian, who taught her ballet, tap and acrobatics. The teacher would fit a roll of music into her player piano and the kids would jump until the roll was finished. That’s where McBride got her stamina.

She started dancing on pointe at age 8, which was all wrong, she says. Much too young. To extend the life of her pricey satin toe shoes, McBride would darn the tips with needle and thread, then slather them with glue and harden them in the oven.“I had never even seen a ballet performed,” she says. “I just knew ballet made me happy.”She studied briefly with a Russian teacher in New York, who told McBride she was cut out to be a Balanchine dancer.

Oh, a Balanchine dancer! McBride remembers marveling. What is that?

She found out when she saw her first ballet: Balanchine’s “Serenade,” a mysterious work tinged with romance and sadness. When the curtain rose on its motionless dancers in long tulle skirts, right arms raised in a mute gesture of yearning, or wonder, “I was fixated,” McBride recalls. “I’d never seen anything so beautiful. The girls, the music, that Tchaikovsky.”

A year later, at 14, she entered Balanchine’s feeder school, the School of American Ballet, on full scholarship.“I worked very hard,” she says. “I loved working hard.”“I never knew I was talented — I just knew that I loved it. Working hard was never exhausting. If anything, I just tried to work harder.”

Growing up without a father had been difficult, she confesses, gazing toward the autumn sun streaming through the restaurant. In McBride’s childhood, few families ever divorced, and all of her friends and neighbors had fathers. But as she dove deeper into ballet, she found a meaningful replacement, a man who she says “is still with me every day of my life.”

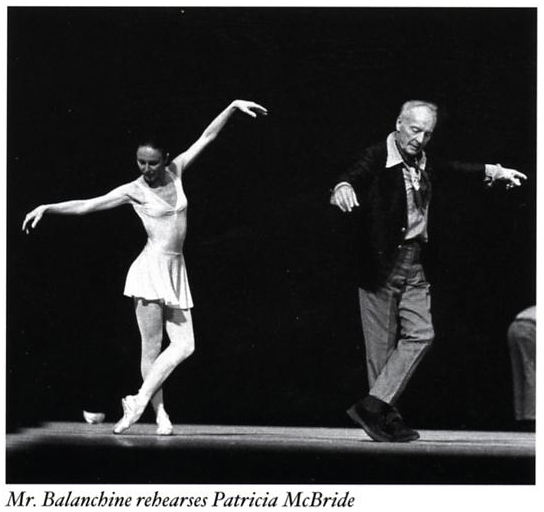

“I felt that Balanchine was my father towards me,” she says of the choreographer, who died in 1983. “He was the person I most admired and looked up to.”

Quiet, patient and endlessly inventive, Balanchine was the idol of so many dancers who knew him. “I just wanted to please him and copy him,” says McBride. “He was so beautiful to watch in motion.”

She sweeps an arm to the side and rolls her shoulder, sketching his elegance with a gesture. “He didn’t want to change you into something you were not. He would let you be yourself.”

He was an Old World gentleman: When he saw her running for a bus in the snow, without boots, he carried her in his arms over the slush. He brought a box of her favorite toe shoes to Russia when the company was on tour there and she danced so much, she wore out the ones she’d packed. She once performed Balanchine’s “Apollo” with Igor Stravinsky conducting his own music; the two men toasted each other with vodka during orchestra breaks.

McBride progressed steadily, rising to the top in an era of iconic ballerinas: Diana Adams, Violette Verdy, Melissa Hayden, Allegra Kent, Suzanne Farrell.

She never had a serious injury. Was that luck, smarts or willpower? “I was determined to dance,” is how she explains it. “That’s why I lasted so long.”

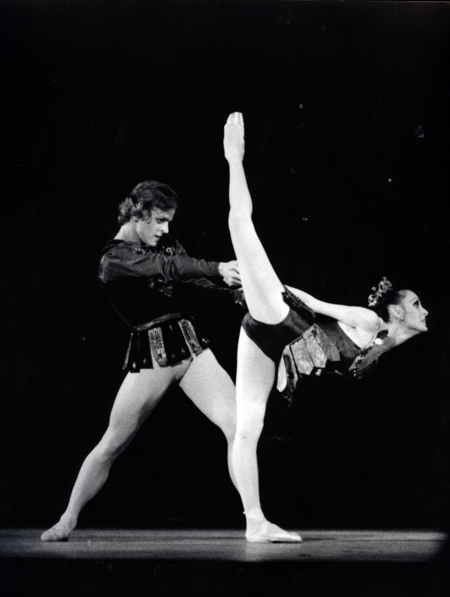

At just over five feet tall, she was the perfect size to dance with the leading men of the day, who were also compact: Mikhail Baryshnikov, Edward Villella, Helgi Tomasson.

“There were times when we were dancing together, she was so enjoying the movement that she would make little sounds, almost like a purr,” recalls Tomasson. “You would hear ‘hmm, hmm,’ during the adagio or whatever it was. All of a sudden you would hear that underneath the music, and it would always make me smile.”

In 15 or so years of dancing together, says Villella, “I never had a cross word with her. She is the most even person imaginable.” The ease of partnering her, he says, “was another amazement.” Villella didn’t know much about partnering when he started dancing with McBride; he was still figuring out how to keep a ballerina from toppling over. McBride was so strong and secure, she made his job easier.

“There are ladies who start to lose their balance and they flail. Or ladies who, when you give them a hand, they clutch.” But with McBride, he says, “it was like a conversation between your fingers. The ease of effort — that’s what Patti was the whole time, because she was a wonderfully trusting partner. She was a dream to work with.”

Sara Mearns, a current New York City Ballet principal, trained with McBride as a young teenager, making the hour-and-a-half commute to Charlotte from Columbia, S.C., every day, six days a week. Without McBride’s teaching, “I wouldn’t be the ballerina I am today,” Mearns says, describing “the joy she had every day. It was such a joyous experience.”

Mearns especially recalls McBride’s focus on presenting oneself to the audience, with a relaxed upper body. And always, a smile.

What McBride emphasizes “is really showing your spirit onstage,” says Alessandra Ball-James, a leading dancer of the Charlotte Ballet. “She wants to see you living onstage.”

Back at the studio, McBride is rehearsing four Sugar Plum Fairies in Bonnefoux’s swift, sweeping “Nutcracker” choreography.

“Soft arms,” she says to Ball-James. “I just felt they were a little stiff.” She flutters her wrists, and it’s like a breeze lifting leaves. “Just so they move a little.”

Ball-James dances again, rippling her arms lightly. It makes all the difference.

“Beautiful!” McBride exclaims. “Good!”

And because it’s true, and also because it’s her nature, she showers pleasure on everyone in the room: “You’re all so good.”

*All images from The George Balanchine Trust unless otherwise noted.

For more of my design inspiration, please follow along on Instagram, Pinterest, Facebook, Twitter and subscribe to Bespoke Banter….Thanks for reading!